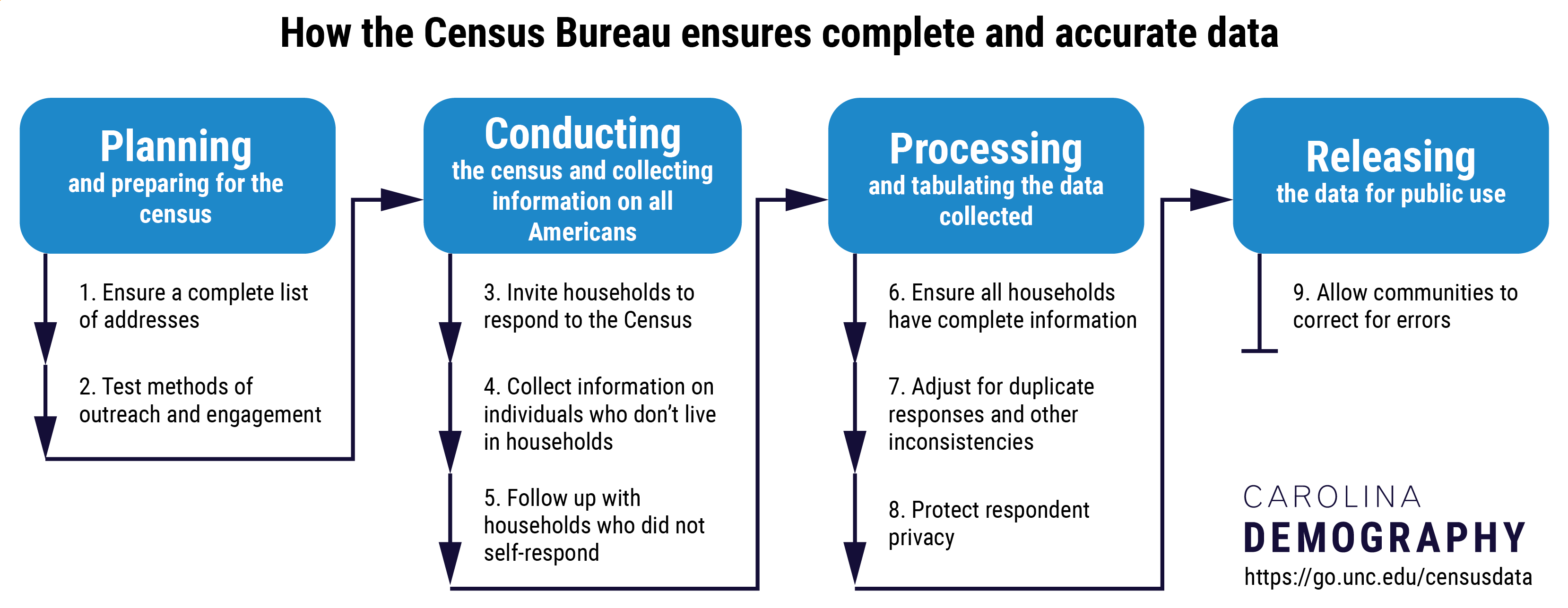

How the Census Bureau ensures complete and accurate data

Once a decade we count everyone living in the United States in the decennial census, as we have done every ten years since 1790. Trying to count all Americans once—and only once—and in the right place is a herculean task. Although we talk about the Census in reference to Census Day (April 1, 2020), the process of counting all Americans begins years before Census Day and continues for years afterwards. We can break down the process of completing the decennial census count into four general phases:

In this post, we outline key steps the Census Bureau takes during each of these phases to ensure that the data collected is as complete and accurate as possible. Throughout all phases, the Census Bureau is continuously evaluating processes to improve the current census operations and plan for the next decennial.

The backbone of the decennial census is the Master Address File (MAF). . This is a database that is meant to contain a complete list of all living quarters, as well as a subset of non-residential addresses. Between 2010 and 2020, the Census Bureau updated and maintained the MAF by:

In addition to these activities, the Census Bureau works with designated local representatives to review the addresses that will be used to conduct the census through the Local Update of Census Addresses.

For the 2020 Census, the Bureau had a list of 151.8 million total addresses, an increase of 15.1 million from 2010. In North Carolina, there were 5.1 million total addresses in 2020, half a million more than the 4.6 million in 2010.

In preparation for the decennial census, the Census Bureau conducts an End-to-End test. This is essentially a “dress rehearsal” to identify any challenges that need to be addressed prior to the full census. The test for the 2020 Census was in 2018 in Providence, Rhode Island.

In addition to the End-to-End Test in 2018, the Bureau also conducted a nationally-representative survey to identify barriers to census participation. to identify barriers to census participation. The results from this survey help the bureau identify key strategies for reaching hard-to-count communities.

Self-response—when individuals fill out the census form for themselves and their households directly—is the most complete and accurate form of census data. The U.S. Census Bureau asks every household to respond and follows up with households that do not respond on their own. In 2020, households were able to self-respond online, by phone, or by mail. The Bureau also provided the following resources to motivate self-response in 2020:

Nationally, 65.3% of all addresses were counted by self-response, a four-percentage point increase over 2010 (61.1%). In North Carolina, the proportion of addresses counted by self-response increased by 4.7 percentage points, rising from 57.1% in 2010 to 61.8% in 2020.

The Bureau has a number of special operations to count individuals who do not live in households. These include:

Every household that did not self-respond to the census (see Step 3, above) enters the Census Bureau’s non-response follow-up (NRFU) universe. During NRFU, the Census Bureau sends a trained enumerator door-to-door to collect census responses directly. If the housing unit does not respond after multiple attempts (three in 2020), the enumerator may use a proxy respondent, such as a neighbor or landlord, for information about the household and who lives there. When households did not respond in 2020, the Bureau also used available data from government administrative records and third-party sources to “identify vacant households, determine the best time of day to visit a particular household, or to count the people and fill in the responses with high-quality data from trusted sources” (page 16). In 2020:

Despite the Bureau’s best efforts, some households do not respond to the census and there are no proxy respondents or high-quality administrative records to fill in the gaps. When this happens, the Bureau uses a statistical technique known as imputation to ensure a response for all housing units; imputation “makes the overall dataset…more accurate than leaving the gaps blank.” Specifically, the Census Bureau does count imputation to determine whether a housing unit is occupied and how many people live there by using information on nearby, similar neighbors. In 2020, the Bureau also had to implement count imputation for group quarters (e.g., nursing homes, dormitories, and prisons) due to pandemic-related challenges in counting these facilities.

In addition to count imputation, the Bureau also sometimes uses characteristic imputation to fill in information on missing characteristics of individuals living in housing units and group quarters, such as age and sex. The Bureau uses multiple techniques for characteristic imputation.

While some households don’t respond to the census and require imputation, some individuals are counted multiple times, such as college students reported at their campus residence and by their parents. In other cases, there are multiple responses for one address. The Bureau implemented multiple techniques to adjust for duplicate responses in the 2020 Census.

Part of the reason why the Bureau is able to collect and provide detailed information for communities is because of its commitment to protecting the privacy and confidentiality of responses. During the processing phase, the Bureau used to swap some households to ensure that individual respondents could not be identified. The National Conference of State Legislatures provides a hypothetical example:

“…consider a census block with just 20 people in it, including one Filipino American. Without any disclosure avoidance effort, it might be possible to figure out the identity of that individual. With data swapping, the Filipino American’s data might be swapped with that of an Anglo American from a nearby census block—a census block where other Filipino Americans reside. The details for the person would be aggregated with others, and therefore not identifiable, and yet the total population in both census blocks would remain accurate.”

This helps to ensure a complete census with some tradeoffs for accuracy; without privacy protections, the details of the population in small characteristics could be suppressed completely.

In 2020, in response to the increasing power of modern computers, the Bureau is implementing a new disclosure avoidance system designed to better protect respondents. This new system means that data for some small areas like census blocks may look “fuzzy,” meaning the data won’t seem quite correct; for example, childen may appear to live alone or households may seem implausibly large. The Bureau advises that users aggregate blocks to larger areas such as the census tract, cities, and counties for higher accuracy.

(A note for technical users here: The 2020 Census is different than previous Censuses because we have more information about its disclosure steps. The current system can be publicly interrogated and individuals with computing skills can process this information to calculate various uncertainty metrics and provide clearer information about the underlying uncertainty to redistricters and other data users. (Think of it as akin to what’s needed to produce Margins of Error.) This lets us know the limits of the data and offers transparency that we’ve not had with prior noise injection methods.)

Despite all this work, there are always some errors. Each decade, the Census Bureau conducts a Census Count Question Resolution (CQR) program. This provides an opportunity for local governments to “request a review of their official 2020 Census results and to help ensure that housing and population counts are correctly allocated.” Any changes made under CQR would affect federal funding but would not affect apportionment or redistricting.

Need help understanding population change and its impacts on your community or business? Carolina Demography offers demographic research tailored to your needs.

Contact us today for a free initial consultation.

Contact UsCategories: Census 2020

The Center for Women’s Health Research (CWHR) at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine released the 12th edition of our North Carolina Women’s Health Report Card on May 9, 2022. This document is a progress report on the…

Dr. Krista Perreira is a health economist who studies disparities in health, education, and economic well-being. In collaboration with the Urban Institute, she recently co-led a study funded by the Kate B. Reynolds Foundation to study barriers to access to…

Our material helped the NC Local News Lab Fund better understand and then prioritize their funding to better serve existing and future grant recipients in North Carolina. The North Carolina Local News Lab Fund was established in 2017 to strengthen…

Your support is critical to our mission of measuring, understanding, and predicting population change and its impact. Donate to Carolina Demography today.