Guide: Opportunity Youth in NC

When the myFutureNC state dashboard launched in February 2020, we tracked an indicator called “disconnected youth,” which we defined as the percent of North Carolina’s 16-19-year-olds who were neither in school or working full or part time.

The definition focused on the 16-19 age range because that was the age range used by the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey in their subject table. (Specifically, we were looking at the 5-Year ACS in Table B14005: Sex by School Enrollment by Educational Attainment by Employment Status for the Population 16 to 19 Years.)

However, we have since expanded the age range of youth who are considered disconnected to encompass 16-24. This wider age range points a more accurate picture of youth disconnection and aligns with national conventions. Youth.gov, the Aspen Forum for Community Solutions, and the Congressional Research Service all use the wider 16-24 age range in their analysis of disconnected youth.

This means we are revising the data related to disconnected youth on our county-level profiles and on the main myFutureNC dashboard. We are also renaming the indicator to “opportunity youth.” This term is widely used, and reframes the issue.

In their white paper “Achieving Collective Impact for Opportunity Youth,” Lili Allen, Monique Miles and Adria Steinberg describe it this way:

Many of them are “connected”—to friends, neighborhoods, churches, families, and local community-based organizations. But the institutions, organizations, and public systems that could help them achieve higher levels of education, training, and jobs are themselves disconnected from one another. Recognizing this reality, many advocates have abandoned the term “disconnected youth.” Instead, we favor “opportunity youth,” a phrase that calls attention to the opportunities these young people seek and that should be opened up for them.

This post details what the change in definition and wider age scope means for trends related to this population in North Carolina.

Opportunity youth are defined as individuals ages 16 to 24 who are neither in school or working full or part time. Individuals who are not working for any reason, whether that is unemployment or incarceration, are included in this definition if they are not in school.

Unemployment and a lack of educational attainment are also linked to depression, anxiety, and isolation. The limited education, lack of work experience, minimal professional networks, and social exclusion of opportunity youth have consequences into adulthood and may affect earnings and self-sufficiency, physical and mental health, and relationship quality and family formation.

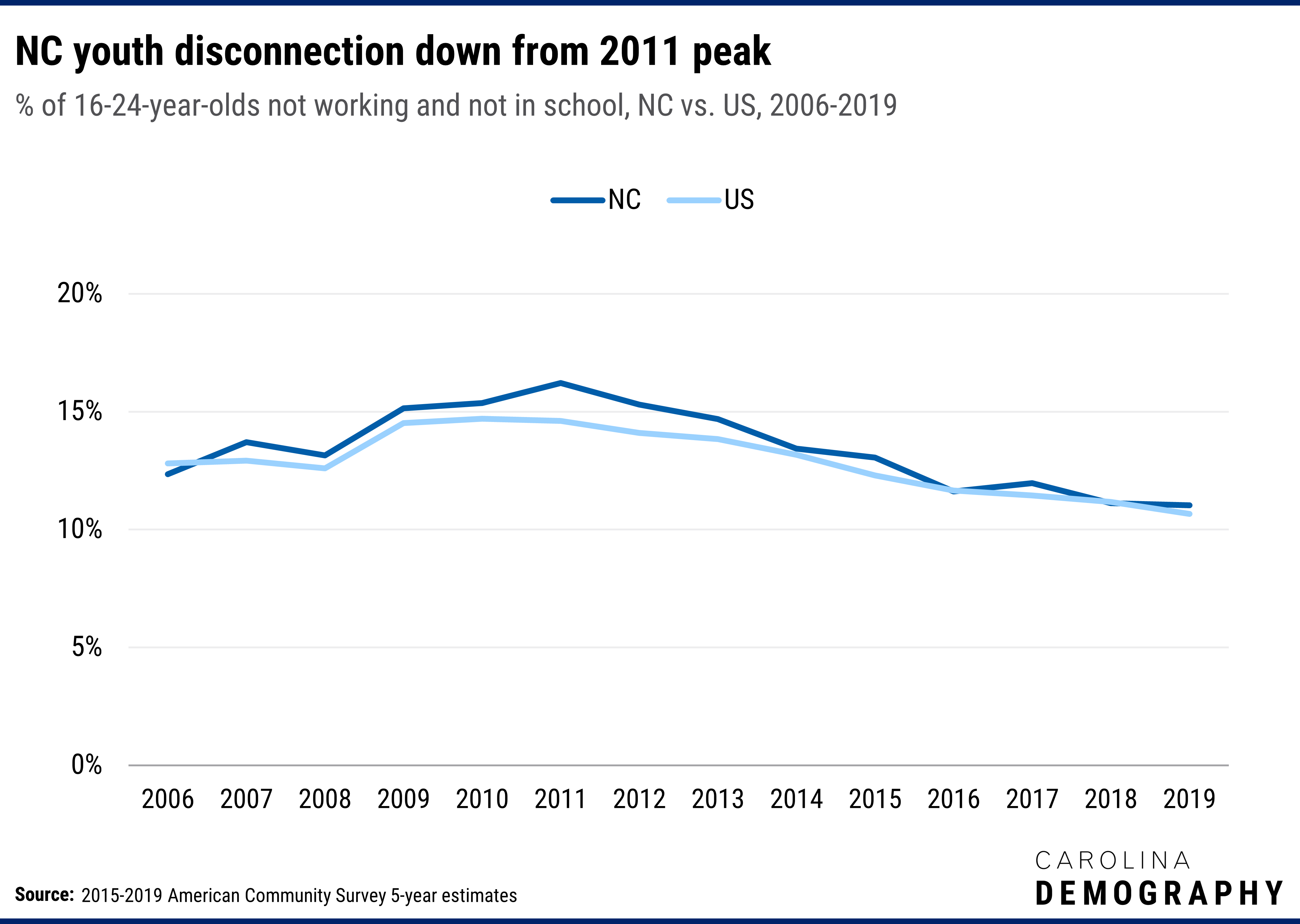

North Carolina’s rate of opportunity youth was about the same as the national average in 2019—11.0% of people aged 16-24 were not working or employed versus 10.8% nationally.

This is a shift. Almost every year since 2006, a higher percentage of North Carolinians between 16-24 were not employed and out of school than the national average, though the rate has gotten closer to the national average since 2016. Our state’s rate also follows national patterns: it increased after the Great Recession in 2008 – e.g. higher rates of young people out of work and school – and started to shrink after 2011. As of 2019, opportunity youth rates were lower than they were before the Great Recession.

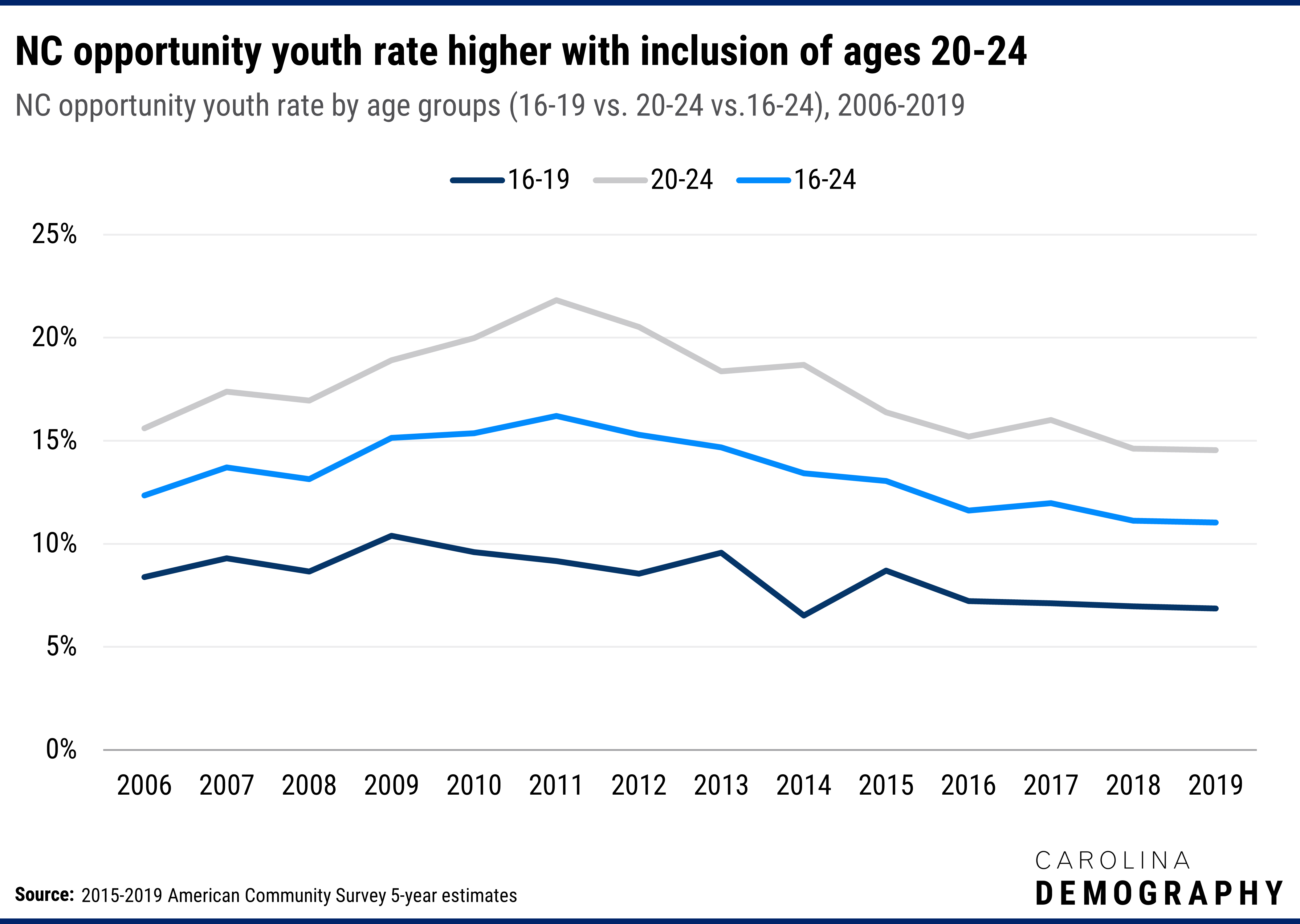

Statewide, the opportunity youth rate increased from 6.9% (for 16-19 years old) to 11.0% (for 16-24 years old) in 2019. We see differences within the age range of 16-24. People aged 20- 24 have higher disconnection rates than individuals 16-19; 14.5% of North Carolinians aged 20-24 were disconnected verses 6.9% of 16-19 years old in 2019. Compared to 16-19 years old, youth aged 20-24 years old are more likely finished high school and struggling with going to college or finding a job. This indicates the period after high school education is risky for youth to be disconnected.

Adding the 20-24 age range into the analysis doesn’t change how North Carolina’s rate compared to the national average. However, the opportunity youth rate for 16-24-year-olds stays elevated after the Great Recession for a longer period of time than the opportunity youth rate for just 16-19-year-olds. One potential reason for this difference may be that the younger age group (16-19) has a stronger connection to school: many of these individuals are still enrolled in high school and worsening economic conditions, such as during the Great Recession, may lead potential dropouts to stay enrolled; this option is not available to the older age group (20-24).

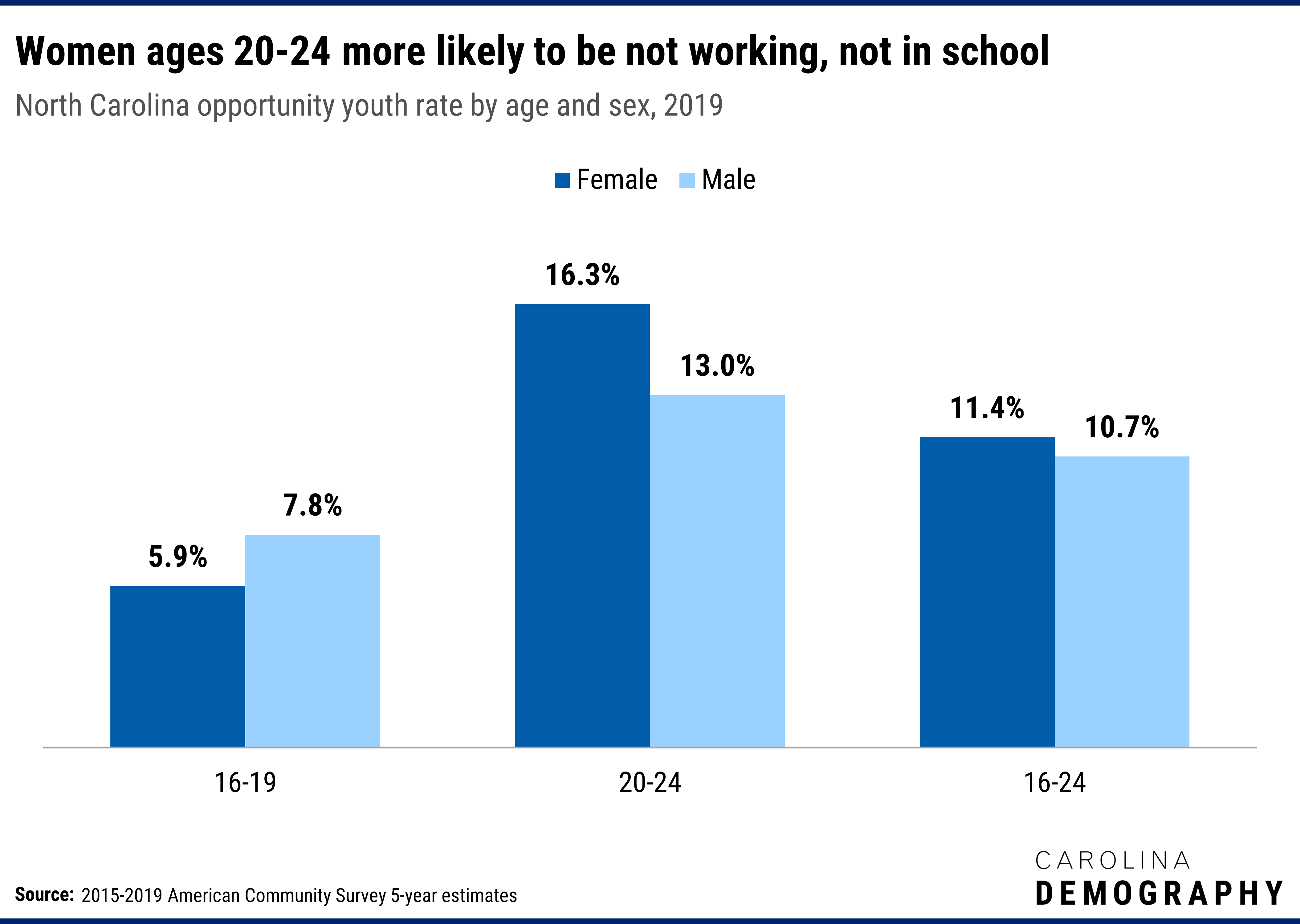

North Carolina men aged 16-19 have higher rates of disconnection than women – 7.8% vs. 5.9%. The reverse is true for the age range 16-24: we see North Carolina females having higher rates of disconnection than men (11.4% vs. 10.7%).

It is worth noting that the disconnection rate of females aged 20-24 years old was almost two times more than the rate of 16-19 years old females (16.3% vs 5.9%). This may indicate the possible impact of childbearing and subsequent childcare responsibilities on females aged 20-24 years old.

Statewide, opportunity youth had a lower median total family income compared to non-opportunity youth in 2019 ($43,000 vs. $69,200). Also, opportunity youth had a higher percentage of people living in poverty than non-opportunity youth in 2019 (31% vs 16%).

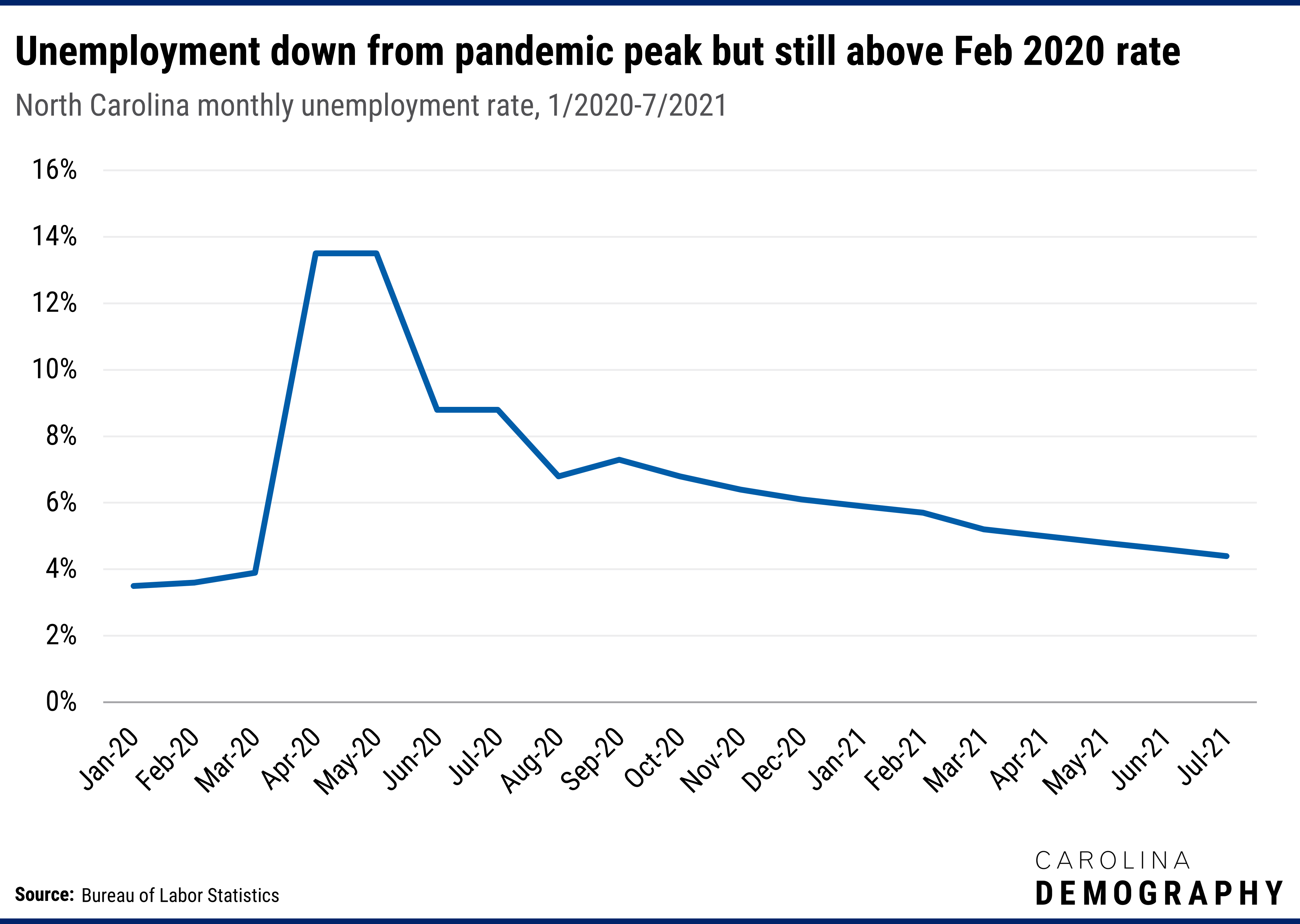

We are still in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic but can already see potential impacts for opportunity youth. The Measure of America of the Social Science Research Council an increased unemployment rate and shifting schools online may have a negative impact.

The pandemic had an immediate impact on job opportunities, leading to widespread unemployment and job losses. And, unlike the Great Recession, these economic impacts were not accompanied by an increase in enrollment in educational programs. As a results, we could see significant increases in the number and share of individuals ages 16-24 who are disconnected from work and school.

Economic Policy Institute reported that “the overall unemployment rate for young workers ages 16–24 jumped from 8.4% to 24.4% from spring 2019 to spring 2020” and “young workers are more likely to be in jobs impacted by COVID-19”.

We also see missing students. Research from Bellwether Education Partners estimates that there were 3 million missing K-12 students between March to October in 2020, writing “For approximately 3 million of the most educationally marginalized students in the country, March might have been the last time they experienced any formal education — virtual or in-person.” According to their research, marginalized students (e.g., living in a low-income household) are more likely to be not attending schools because of lack devices and technology to access online learning during the pandemic.

At the postsecondary level, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reported that the number of immediate fall enrollments—high school graduates transitioning directly into college—declined by 6.8% between Fall 2019 and Fall 2020.

In the 2020–21 Performance of North Carolina Public Schools report, NC Department of Public Instruction noted that performance on all end-of-grade and end-of-course declined compared to the 2018–19 school year.

Moreover, the pandemic created social isolation which may impact youth mental health, generated barriers, confusions, and inaccessible learning services to students, especially for those students who are English learners, students with disabilities, and students in foster care and experience homeless.

Obviously, all of these factors would negatively impact youth’s study outcomes and academic abilities move to the next educational level. Even with increasing vaccinated rate and increasing classes moved to face-to face, with masks and social distancing rules, classes are not likely to be the same as before.

COVID-19 has also created challenges to understanding these patterns. The data that we use to monitor opportunity youth in North Carolina are drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS). The Bureau recently announced that it would not release the 2020 1-Year ACS due to pandemic impacts on data collection.

Need help understanding population change and its impacts on your community or business? Carolina Demography offers demographic research tailored to your needs.

Contact us today for a free initial consultation.

Contact UsCategories: Education

The Center for Women’s Health Research (CWHR) at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine released the 12th edition of our North Carolina Women’s Health Report Card on May 9, 2022. This document is a progress report on the…

Dr. Krista Perreira is a health economist who studies disparities in health, education, and economic well-being. In collaboration with the Urban Institute, she recently co-led a study funded by the Kate B. Reynolds Foundation to study barriers to access to…

Our material helped the NC Local News Lab Fund better understand and then prioritize their funding to better serve existing and future grant recipients in North Carolina. The North Carolina Local News Lab Fund was established in 2017 to strengthen…

Your support is critical to our mission of measuring, understanding, and predicting population change and its impact. Donate to Carolina Demography today.